Create Synchronous Learning That Works Well

Synchronous digital learning elements are used live, with participants participating at the same time, typically from different places. Synchronous elements allow participants to learn from and collaborate with participants and a facilitator/trainer/instructor and get help and questions answered in real time. Typical synchronous tools used for learning include live meetings, instant messaging, and virtual classrooms.

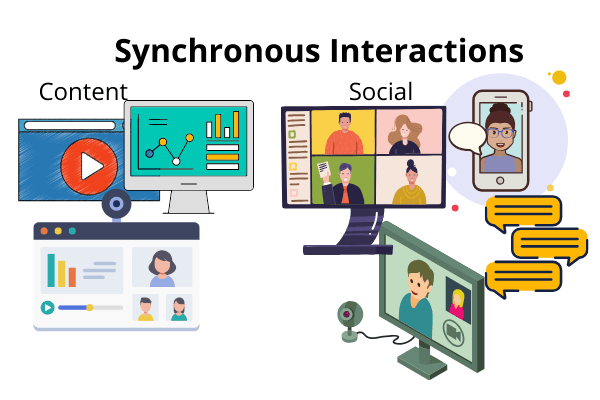

Synchronous learning is extremely popular because it feels a lot like classroom learning. In fact, research often calls synchronous learning a special case of classroom learning. As a result, synchronous sessions are often called VILT, or Virtual Instructor-Led Training. The image below indicates the range of synchronous content and social interactions.

(Common content and social synchronous interactions)

Synchronous sessions may be recorded, which makes them useful for people who cannot attend or who wish to view the session again, but it’s important to note that recorded sessions are asynchronous as they no longer include real-time interactions. As a result, recorded synchronous sessions do not have the social interaction and immediacy benefits of live synchronous sessions. But they do have the flexibility benefits of asynchronous learning elements.

Let’s consider a situation where synchronous learning would add real value. An organization has been preparing to train people on the company’s updated financial software. While working from home because of COVID-19, trainers have added people throughout the company to their bi-weekly live meetings. Having people involved from inside and outside the home office will help them have system update experts in all their locations.

The bullets below show how the training group has decided to meet the training needs of this organization. They will build online courses with mostly asynchronous elements (the first three bullets) and supplement with synchronous elements (the fourth and fifth bullet) to add immediacy and interaction.

- On-demand, short video demos showing how to perform commonly performed tasks

- Practice exercises for different company functions on their specific tasks

- Job aid(s) to help people perform the exercises and tasks

- Live sessions in various time zones to introduce the software, videos, and exercises and answer questions

- Live sessions in various time zones to support the specific needs of different company functions

This is not the only way to build this training, of course, but it’s a good starting plan for combining the benefits of asynchronous and synchronous learning. In this article, I’ll discuss the benefits and challenges of using synchronous elements.

| In Part 1, I discussed digital learning tools used asynchronously (on demand, when and where the user chooses) and synchronously (live, at the same time for all users). Both modes support learning, but differently, according to research. In Part 2, l analyzed how asynchronous and synchronous tools support different learning interactions and what each mode is best for. Part 3 describes the use and selection of asynchronous elements.

These are some key ideas discussed in Parts 1-3 that are helpful for understanding the ideas in Part 4:

|

Benefits Of Synchronous Learning

Because the advantages and limitations of asynchronous and synchronous counterbalance each other, many online and blended learning researchers say we should combine them. In the earlier training example, that’s exactly what the company decided to do. The asynchronous elements meet the needs of different company functions and allow people to learn when and where they are able. Synchronous elements, such as live sessions, reduce social isolation, provide immediate help, and allow people to learn from each other.

This table recaps what research shows are primary advantages of synchronous learning.

| Synchronous Learning Benefits | |

|---|---|

| Immediacy | Social Interaction |

|

|

Let’s talk more about immediacy and social interaction, as they offer important benefits for digital instruction.

Immediacy And Social Interaction

Moore tells us that content and social interactions “at a distance” can create physical and psychological barriers that produce (perceived or real) learning difficulties. There are many aspects of teaching and learning that change when content and social interaction are at a distance, including communications, tools, practices, familiarity, accessibility, and more. According to Moore, we must minimize the feeling of distance or risk isolation, which leads to lessened attention, motivation, and engagement.

Immediacy refers to actions that reduce perceived distance, such as fast response time and real-time communication. When you ask a question, for example, and no one answers for three days you may have figured it out yourself or moved on to other concerns. In any event, the lack of response feels isolating, and isolation generally feels bad. Research shows that immediacy often improves learning, so adding synchronous sessions can be extremely valuable.

The benefits of synchronous learning are super important and require specialized knowledge and skill to gain. Designers and instructors, therefore, must be taught how to use immediacy behaviors such as:

- Encouraging questions, ideas, and input

- Encouraging peer help and insights

- Discussing participant situations

- Using participant names

- Offering gentle and valuable feedback

- Asking for participant opinions, insights, and feelings

- Using appropriate tools (such as chat) to offer valuable social interactions

Moore tells us one of the most important interactive elements in technology-mediated learning environments is interacting with others. Well-designed synchronous instruction, aided by live communication tools (such as text chat, audio chat, and video chat), makes these interactions possible. The right kinds of interactions help participants deeply process what they are learning. Deep processing is needed to apply what we are learning. (See the explanation of deep processing in Part 3.)

It’s critical, then, to make sure that designers and instructors know how to teach well in live sessions. Teaching in this environment is not like teaching in a face-to-face classroom and without sufficient knowledge and skill, these sessions are likely to have myriad problems.

Most asynchronous instruction in the workplace, unfortunately, does not provide options for immediacy and social interaction. Sharing insights with others allows for different points of view, different experiences, varying contexts, valuable resources, getting unstuck, and more. This is a major reason why research suggests blending asynchronous and synchronous learning.

Challenges With Synchronous Learning

The major advantage of synchronous learning is social interaction and immediacy. But it’s important to realize that there are also barriers to overcome. We’ve already described the potential barrier of social isolation, which is common in digital learning. Synchronous learning has the great potential to overcome this barrier, when designers and instructors are trained to use the best teaching methods for synchronous tools.

Research discusses other barriers to desirable outcomes, especially technical barriers, multitasking, unnecessary cognitive load, and limited instructor skills. I’ll discuss these barriers next and will apply my discussion specifically to the virtual classroom, as that’s the most common tool used for synchronous learning in the workplace.

Technical Difficulties

Synchronous learning is mediated by technology. Technology can assist in teaching and learning, but it also generates technical problems. If you’ve attended a synchronous session with technical glitches, you’ve experienced this reality. The following technical issues are pointed out in numerous research discussions.

- Problems using the platform, tools, and interface

- Bandwidth and connection difficulties

- Need for specialized equipment (for example, USB headsets), design, and facilitation

To reduce technical difficulties, we should:

- Keep the interface as uncomplicated and consistent as possible

- Train participants and instructors on how to use the interface and tools

- Consistently use the tools so their use becomes automatized

Multitasking

Trabinger’s research specifically discusses problems with multitasking—called task switching in research, as we are unable to multitask—in the virtual classroom. Research shows that participants often task switch during technology-mediated instruction. And that task switching has numerous negative outcomes, including reduced performance, increased time for completing a task, and reduced retention. Because of the extremely negative impacts of task switching, it’s important for us to do what we can to combat it.

To reduce multitasking:

- Analyze what people need and deliver exactly that

- Keep people involved

- Don’t embarrass people for task switching, but design to make task switching less likely

Cognitive Load

Cognitive load is the total amount of mental effort being used by working memory (the memory needed to process and make sense of information). Working memory must process and understand information to learn. When there are too many or kinds that aren’t valuable, people feel overwhelmed and cannot learn. When we include sources of unnecessary cognitive load, there is less left for learning.

Virtual classroom platforms are usually complex and require mental effort to use for various tasks. For example, how do I ask/answer questions? How do I get help if I am not hearing the instructor? How do I post questions? We must be careful about adding unnecessary sources of cognitive load.

To eliminate unnecessary cognitive load, we can:

- Provide an overview that explicitly shows the organization of the session

- Use clear and consistent headings that match the overview

- Limit the content to only what is needed

- Write concisely and use consistent language

- Provide clear, concise instructions

- Make sure that information that goes together (e.g., is needed to understand each other) is integrated

- Use images to show relationships

Limited Instructor Skills

Many researchers discuss the difficulty of teaching (well) and the need for deep training and practice as a barrier to effective virtual classroom use. Instructing in the virtual classroom requires intensive preparation and demanding real-time facilitation skills. In addition to the more general topic knowledge and understanding of participant needs, there are specific-to-virtual classroom skills, as discussed by Bower and others, including:

- Planning sessions so there is less likelihood of technology problems and multitasking

- Designing content to optimize learning and understanding and reducing the potential for overload

- Using virtual classroom tools properly

- Moderating/facilitating social interaction

- Managing participants, interactions, and technology

Selecting Synchronous Learning Elements

The following two tables show common synchronous content and social interactions and their typical uses, advantages, and problems.

| Typical Content Interactions | Common Uses | Typical Advantages/Problems |

|---|---|---|

| Screen sharing/slides |

|

|

| Questions, polls, quizzes, other activities |

|

|

(Synchronous Content Interactions)

| Typical Social Interactions | Common Uses | Typical Advantages/Problems |

|---|---|---|

| Chat |

|

|

| Polls |

|

|

| Breakout rooms |

|

|

(Synchronous Social Interactions)

The following table breaks typical synchronous interactions into various levels (know–understand–apply) so we can see how synchronous interactions support learning at the levels described by Furst.

| Interaction Levels | Example Synchronous Interactions |

|---|---|

| Apply | Cases, problems, plans, troubleshooting, tasks |

| Understand | Demos, questions and answers, discussions, quizzes |

| Know | Presentations, links to more information, knowledge checks, remembering exercises (retrieval practice), quizzes |

Level of Synchronous Interactions, adapted from Dunlap and Stouppe:

The key insight in this article, I hope, is that synchronous learning can provide very important-to-learning benefits and these benefits can help the key challenges of asynchronous learning. And asynchronous learning provides key benefits and these benefits can help the key challenges of synchronous learning. To gain these benefits and help these challenges requires knowing how to do them well.

In my final article on using digital modalities, Part 5, I’ll talk more about blending asynchronous and synchronous elements to meet specific learning needs. I’d love to discuss the topics in this series in an upcoming live session. If you’re interested, join my email list, and I’ll contact you when I set these up.

Thanks to Karen Hyder (@karenhyder), my #deeperlearningatwork colleague who has been working with the virtual classroom for 20 years. She reviewed this article and provided insights to make it better.

References:

- Adams, Rebecca L. (2010). Design practices business organizations employ to deliver virtual classroom training, Graduate Research Papers. 122. https://scholarworks.uni.edu/grp/122

- Anderson, L. A. (nd). The effect of synchronous and asynchronous communication on social presence and isolation in online education.

- Arbaugh, J. B. (2001). How instructor immediacy behaviors affect student satisfaction and learning in web-based courses. Business Communication Quarterly, 64, 42-54.

- Arbaugh. J. B. (2000), Virtual classroom characteristics and student satisfaction with Internet-based MBA classess. Journal of Management Education, 24, 32-54.

- Bernard, R. M., Abrami, P.C., Wade, A., & Borokhovski, E. (2004). The effects of synchronous and asynchronous distance education: A meta-analytical assessment of Simonson’s “equivalency theory,” Association for Educational Communications and Technology, 27th, Chicago, IL.

- Bower, M. (2008). Designing for interactive and collaborative learning in a web conferencing environment. Doctoral dissertation, Macquarie University, Sydney.

- Bower, M. (2011). Synchronous collaboration competencies in web-conferencing environments—their impact on their learning process. Distance Education, 32(1), 68-83.

- Burak, Lydia J. (2012). Multitasking in the university classroom. In Movement Arts, Health Promotion and Leisure Studies Faculty Publications. Paper 74.

- Carrell, L.J. and Menzel, K.E. (2001). Variations in learning, motivation, and perceived immediacy between live and distance education. Communication Education, 50, 230-241.

- Chou, C. C. (2002). A comparative content analysis of student interaction in synchronous and asynchronous learning networks, Hawaii International Conference on System Sciences.

- Clark, R. E. 1983. Reconsidering research on learning and media. Review of Educational Research, 53 (4): 445-459.

- Clark, R., & Kwinn, A. (2007). The New Virtual Classroom. San Francisco: Pfeiffer.

- Dunlap, J. C., Sobel, D. & Sands, D. I. (2007). Designing for deep and meaningful student-to-content interactions. TechTrends, 51(4), 20-31.

- Freitas, A. F., Myers, S. A., & Avtgis, T. A 1998. Student perceptions of instructor immediacy in conventional and distributed classrooms. Communication Education, 47: 366-372.

- Furst, E. (nd). Introduction: Learning in the brain. Teaching with Learning in Mind. https://sites.google.com/view/efratfurst/teaching-with-learning-in-mind

- Furst, E. (nd). Unerstanding ‘understanding.’ Teaching with Learning in Mind. https://sites.google.com/view/efratfurst/understanding-understanding

- Furst, E. (nd). Meaning first. Teaching with Learning in Mind. https://sites.google.com/view/efratfurst/meaning-first

- Gorham, J. 1988. The relationship between verbal teacher immediacy behaviors and student learning. Communication Education, 37, 40-53.

- Grant, M., & Cheon, J. (2007). The value of using synchronous conferencing for instruction and students. Journal of Interactive Online Learning, 6(3), 211-226.

- Hsieh, Y. H. & Tsai, C. C. (2012). The effect of moderator’s facilitative strategies on online synchronous discussions, Computers in Human Behavior, 28(5), 1708–1716.

- Hurst, B., Wallace, R., & Nixon, S. B. (2013). The Impact of Social Interaction on Student Learning. Reading Horizons: A Journal of Literacy and Language Arts, 52 (4).

- Judd, T. (2015). Task selection, task switching and multitasking during computer-based independent study. Australasian Journal of Educational Technology, 31(2).

- Junco, R., & Cotten, S. (2011). A Decade of Distraction? How Multitasking Affects Student Outcomes. 2011 A Decade in Internet Time Symposium on the Dynamics of the Internet and Society, Oxford, UK.

- Kalyuga, S. (2014). Managing cognitive load when teaching and learning e-skills. Proceedings of the e-Skills for Knowledge Production and Innovation Conference 2014, Cape Town, South Africa, 155-160.

- Kirschner, P., & van Merriënboer, J. (2013). Do Learners Really Know Best? Urban Legends in Education. Educational Psychologist, 48(3), 169-183.

- LaRose, R., & Whitten, P. 2000, October. Rethinking instructional immediacy for web courses: A social cognitive exploration. Communication Education, 49 (4): 320-338.

- Loch, B., & Reushle, S. (2008). The practice of web conferencing: Where are we now?, Annual Conference of the Australasian Society for Computers in Learning in Tertiary Education (ASCILITE 2008), Melbourne, Australia, 562-571.

- Martin, F., Parker, M., & Deale, F. (2012). Examining interactivity in a synchronous virtual classroom. The International Review of Research in Open and Distributed Learning, 13(3), 227-261.

- Mayr, U. & Kliegl, R. (2000). Task-set switching and long-term memory retrieval. Journal of Experimental Psychology: Learning, Memory, and Cognition, 26, 1124-1140.

- Messman, S.J. and Jones-Corley, J. (2001). Effects of communication environment, immediacy, communication apprehension on cognitive and affective learning. Communication Monographs, 68, 184-200.

- Moore, M. (1997). Theory of transactional distance. in Keegan, D., (ed.) Theoretical Principles of Distance Education. Routledge, 22-38.

- Ng, K. (2007). Replacing face to face tutorial by synchronous online technologies: Challenges and pedagogical implications. International Review of Research in Open and Distance Learning, 8(1), 1492-3831.

- Offir, B., Lev, Y., & Bezalel, R. (2008). Surface and deep learning processes in distance education: Synchronous versus asynchronous systems. Computers & Education. 51, 1172–1183.

- Ophir, E., Nass, C., & Wagner, A. (2009). Cognitive control in media multitaskers. Proceedings of National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America, (106)37, 15583-15587.

- Rogers, R. & Monsell, S. (1995). The costs of a predictable switch between simple cognitive tasks. Journal of Experimental Psychology: General, 124, 207-231.

- Rosen, C. (2008). The Myth of Multitasking. The New Atlantis, 105-110.

- Schifter, C. C. (2000). Faculty participation in asynchronous learning networks: A case study of motivating and inhibiting factors. Journal of Asynchronous Leaning Networks, 4(1).

- Swan, K. 2001. Virtual interaction: Design factors affecting student satisfaction and perceived learning in asynchronous online courses. Distance Education, 22, 306-331.

- Shank, P. (2017). Attention And The 8-Second Attention Span, eLearning Industry.https://elearningindustry.com/8-second-attention-span-organizational-learning

- Stouppe, J. (1998). Measuring interactivity. Performance Improvement, 37(9), 19–23.

- John Sweller, J. (2010). Element interactivity and intrinsic, extraneous, and germane cognitive load, Educational Psychology Review, 22(2), 123–138.

- Trabinger, K. L. (2016). Encouraging learner interaction, engagement and attention in the virtual classroom. Doctoral dissertation, University of Southern Queensland.

- Thompson, S. (2017). Isolation: A barrier of virtual distance learning, Medium. https://medium.com/@samuelbthompson/isolation-a-barrier-of-virtual-distance-learning-bcfbe95f7f8a

- Todhunter, S., & Pettigrew, T. (2008). VET goes virtual: Can web conferencing be an effective component of teaching and learning in the vocational education and training sector? Adelaide, Australia: NCVER.

- Watts, L. (2016). Synchronous and asynchronous communication in distance learning: A review of the literature.

- Witt, P. L., & Wheeless, L. R. 2001. An experimental study of teacher’s verbal and nonverbal immediacy and student’s affective and cognitive learning. Communication Education 50(4), 327-342